The Art of Making

Foster + Partners’ head of industrial design shares how the Paris Agreement and a chair rig led to the Leva chair created for Mattiazzi

Making is at the heart of UK-based architecture and design studio Foster + Partners. Their designs emerge from multiple rounds of prototyping and testing. It’s a process they refer to as “unconscious design,” allowing function to determine form without sacrificing an ounce of beauty. We talked with Mike Holland, head of industrial design at Foster + Partners, about their collaboration with Mattiazzi and how a desire for sustainable timber furniture prompted the design of the Leva chair (available now through Steelcase Marketplace).

360: You’ve been with Foster + Partners for 25 years. How do you keep your approach to design fresh?

Mike Holland: If you look around our model shop, everything is a product of model-making and prototyping. It’s all from 3D printing, CNC machining, handmade modeling and workshops. Everything we do is through making. And that might sound a little obvious, but by making we don’t always consciously style or design our products. We start with rigs and prototypes that allow us to test things, and it’s through that physical relationship of making that the unexpected happens. If you’re just CAD modeling, it’s a very linear process. Through making, things become messier. It allows us to bring in all these different specialties and areas of expertise and that’s where design gets very interesting.

360: One of your recent projects was designing the Leva chair for Mattiazzi. What led you to take on this project?

MH: Over the last few years, we’ve been working on the Paris Agreement and trying to measure a building’s total carbon footprint. We started to realize the interior of a building equates to somewhere around 20% of a building’s embodied carbon footprint, and furniture is a large proportion of that. We made a conscious decision that we wanted to create a low-carbon, comfortable timber chair. When we started to analyze and study the market, we realized there was a place for it, and we made an effort to pursue that as a company.

360: What did the design process look like? Or maybe we should ask: How did you make it?

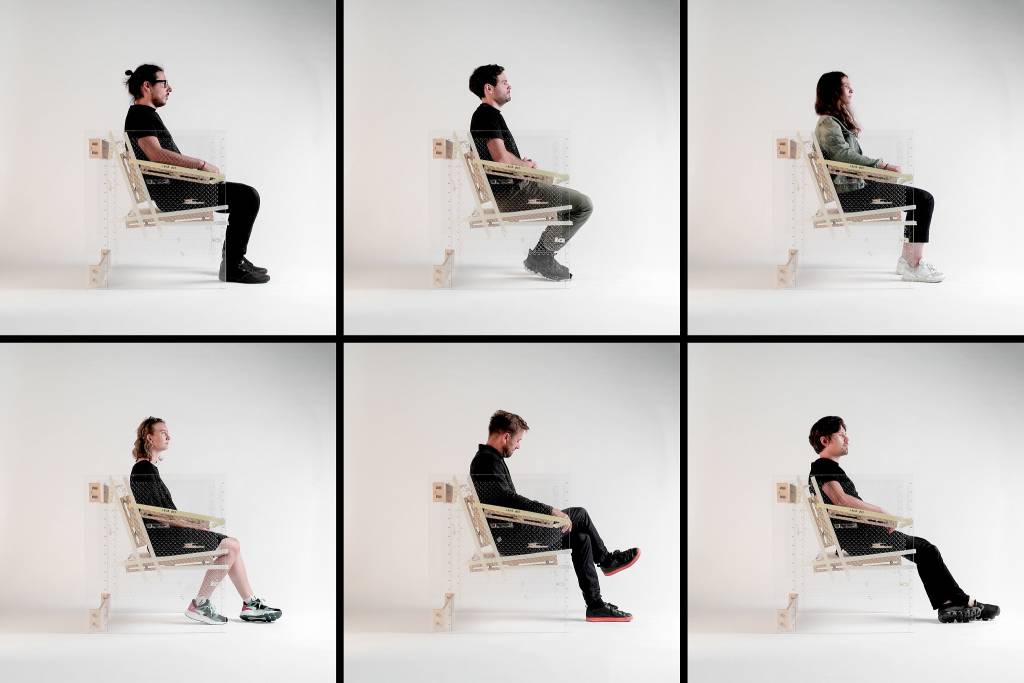

MH: We didn’t sit down and actually design it. We started by creating a chair rig. We had hundreds of people in the office sit in it. And we kept adjusting and refining it until we started to develop this singular line — the armrest and backrest as a single form. We started to look at the angle of the arm, and how the inclination of it made you feel more relaxed. We looked at the contact points, the back, the level of comfort, and it all started to evolve through this rig. It wasn’t consciously styled or shaped. It evolved over time through conversations, arguments and trials to a point where we created a model machined from foam, which we then presented to Mattiazzi.

360: Why did you decide to work with Mattiazzi?

MH: We approached them. Mattiazzi has an incredible knowledge of craft, and they also have developed cutting-edge technology that pushes the boundary of what you can do with timber. That unique combination really sets them apart from other manufacturers. Working with them, you are very much in touch with the process because they have in-house knowledge. So many manufacturers are becoming generalists, but Mattiazzi is a specialist, to an extraordinary level.

360: What is it that makes Mattiazzi so unique?

MH: In a business sense, Mattiazzi has a manufacturing setup that every company in the world should aspire to. They create more energy than they consume. They plant a tree for every one that is cut down for manufacture. They’re very mindful of where they source timber. Everything they do, they do in an incredibly sensitive way. And they don’t even really shout about it — they just do it because it is the right thing to do.

360: How do you describe Leva to people who haven’t seen it before?

MH: From the ergonomic rig we developed, the chair started to take on a form beyond just the curve that ran around its back. We found it to be almost like hand tools or oars — the form was derived from the function. And there is a beauty in that derived form. As the backrest started to take shape, it was as much about the steam-bent process — the way the timber was jointed — as it was about the ergonomics. In a way, doing more with less was the idea behind that. There’s something about the tactility of it, the softness of it.

360: With the new relationship between Steelcase and Mattiazzi, how do you see this chair or future designs fitting into the workplace?

MH: I think we set about designing a chair that would cross the threshold of residential and commercial environments. We didn’t aim purely for commercial interiors. The differences between the two are eroding and offices are becoming far more eclectic. Our hope is that it will sit well within the workplace and the home.

We were also very conscious of the visual noise within a space when designing an interior. Often there are multiple units of the same chair used in an interior space. When testing Leva within some of our projects, we felt it was something that has a presence, but its quiet design also allows it to fill a space in larger numbers.

Learn more about Leva.

Mike Holland is the head of industrial design at Foster + Partners, a global studio for architecture, urbanism and design. He leads a team developing mass manufactured lighting, furniture, building products and transportation, and was the designer behind the Leva Chair, developed in collaboration with Mattiazzi.

Mike Holland is the head of industrial design at Foster + Partners, a global studio for architecture, urbanism and design. He leads a team developing mass manufactured lighting, furniture, building products and transportation, and was the designer behind the Leva Chair, developed in collaboration with Mattiazzi.