Workplace Inclusion: Dismantling Physical, Cognitive, and Cultural Barriers

Steelcase and the Technical University Munich collaborate to address issues of exclusion in the workplace

Designing for inclusion begins with seeing and understanding exclusion. Being intentional about co-creating with people who have traditionally been excluded in the workplace is critical to creating inclusive environments.

Steelcase and the Technical University Munich (TUM) School of Management and School of Engineering + Design came together to address these issues of exclusion in the workplace.

Armed with curiosity and empathy, TUM students embarked on a three-month long project to learn from individuals who had previously been excluded, overlooked, or whose needs were left unmet at their workplace. They also worked with leaders of self-help groups, inclusion managers, activists, local community networks, and experts from the field across Europe.

Students formed research groups with the objective of understanding what elements are required to create more inclusive workspaces in three categories: physical characteristics, cognitive traits, and adherence to certain cultural norms. Through interviews, students investigated needs, trends, and use cases for their three target groups, focusing on common workplace needs such as privacy, accessibility, and wellbeing, among others.

“Working with the students was an eye-opening experience in understanding where different points of inclusion and exclusion happen in the workplace. We worked together in crafting a methodology that could help us uncover the underlying needs of the participants; this meant that students had to continue interviewing users until they dug deeper into the problem space. And in this process, we learned a lot from each other, and even more from the research participants,” says Andrada Iosif, Steelcase Senior Design Researcher.

Anja Pieper, Coach for Neurodiversity Work and Diversity Consultant, illuminates the importance of creating space for those with lived experiences:

“Some of those affected do not even know what their needs are because they have never been in an environment where they were able and allowed to find out before.”

Anja PieperNeurodiversity Work and Diversity Consultant

Student Group Findings

Physical

How might we offer visual and acoustic privacy in an open office environment for employees with physical mismatches?

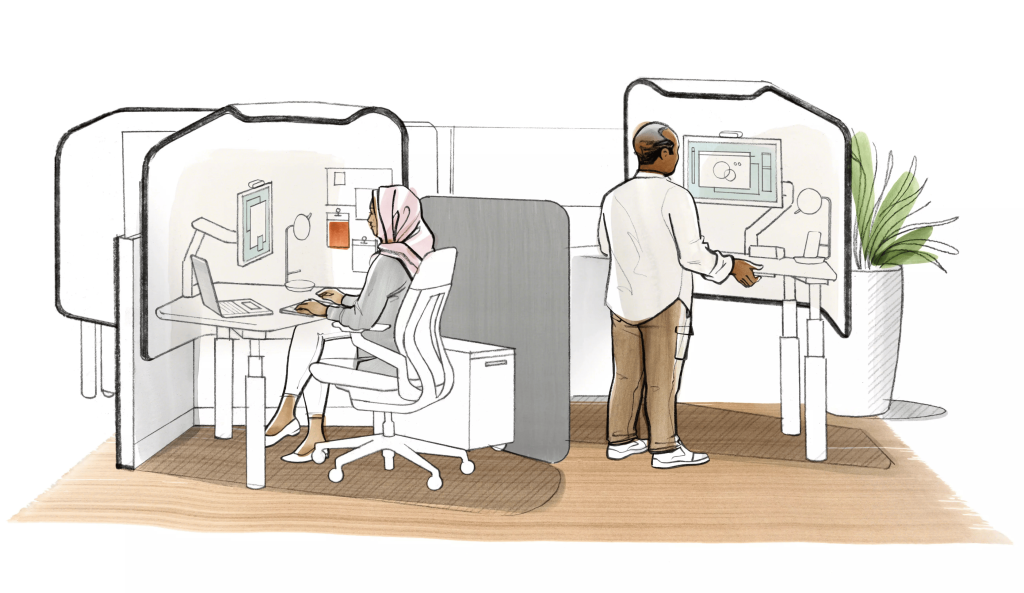

Focusing on privacy, reachability, orientation, and movement, this group explored the physical aspects of inclusivity. Their research aimed to create space solutions that cater to a wide range of physical needs – for example, people with unconventional body sizes, missing limbs, or visual and auditory impairments – ensuring that the office environment is accessible and comfortable for all.

Their findings included ideas such as implementing multisensory guiding strips that are compatible with flexible office concepts for orientation, or designing movable and adjustable furniture to help relieve pain or tension that may be experienced by wheelchair users or prosthetic wearers.

“Throughout our interview process, we learned a tremendous amount about the struggles and wisdom of people with disabilities. We are convinced that there is still much work to be done in the world of inclusive design, which requires the participation of designers with lived experience with disabilities from the very first step,” says Philipp F., TUM student.

Cognitive

How might we provide focus spaces for people with high responsiveness to light?

The second student group conducted interviews focused on the impact of light on the workplace. They worked with users with various neurodiversity conditions – DCD/dyspraxia, autism, mental health, Tourette Syndrome, ADHD, dyslexia, and dyscalculia – to understand how lighting affects individual work, mood, and the ability to focus.

They discovered the need for individuals with cognitive disabilities to have control over lighting conditions, such as the type, color, and intensity of the lighting. They proposed that workplaces create adaptive lighting systems with modifiable features, such as moving lights with adjustable speeds or creating lighting effects with various settings, for example lighting reminiscent of nature.

Cultural

How might we address and mitigate an employee’s need to adapt to a company culture (and not just the other way around?)

The third group of students focused on cultural diversity in office design, interviewing individuals with diverse backgrounds about the role factors such as, ethnicity, gender identity, religion, and social background play in expectations surrounding adherence to certain culture norms.

The group came up with a mix of innovative ideas on how to create more culturally inclusive workplaces, such as providing time for celebrations of different holidays, creating open channels for communication and interaction through events like community dinners, or providing private spaces for prayer and other rituals.

“I was amazed by the eagerness of interviewees to discuss the topic of cultural inclusion, showing it is one that hits close to home. Although there is often still a long way to go, I’m convinced workplaces are moving in the right direction,” reflects Marie V., TUM student.

Designing for inclusion is a journey of empathy, intentionality, and co-creation. Explore Steelcase research to learn more about dismantling barriers and creating spaces where everyone belongs.