Education During and After the Pandemic

The Impact of COVID-19 on Spaces in Schools and Universities

©Copyright Matthias Heisler

The TU Wien (Vienna University of Technology) specializes in architecture and space planning and is one of Austria’s most renowned universities with almost 30,000 students. 360 Magazine spoke with professors Yulia Kartysh and Dietmar Wiegand, who are responsible for project development, to learn how COVID-19 has impacted their work and how they see it influencing the future of education spaces.

360°: How did TU Wien react to the new situation?

Dietmar Wiegand: Until the end of September, we are teaching our students exclusively online. We can easily do this in the School of Architecture and Space Planning and especially in our Project Development Department. Students are working at their own pace with lessons divided into small video sequences and completed with comprehension questions at the end.

We’ve also implemented so-called “self-determined learning.” Students work on a chosen topic during the semester, and we coach them via video conference. Our students accepted the complete switch to e-learning very well because we’ve always integrated e-learning elements into our lectures, so they’re showing just as much motivation as before.

360°: What were your experiences with the complete switch to e-learning?

DW: E-learning is a part of digital teaching and happens in a natural rhythm. Students learn via video when they have time and not according to a given timetable, and teachers can make corrections when they want.

Video conferencing tools are great for connection and are very democratic. Everyone appears in the same size on the screen, and everyone is visible. Even shy students can express themselves, as the moderator can control the conversations. We also learned more about social interaction that normally happens face to face. I don’t have the impression that social interaction has decreased, it’s just different.

However, I miss the creative processes such as brainstorming sessions where we use sticking notes on the wall. So far, we haven’t been able to do that online very well; maybe we are still lacking practice. To be innovative as a group, we have started to meet in the office again. It is simply working better when all participants are in the same room.

With everyone online, a lot has changed in terms of technical infrastructure at the university. We did not know in detail what our own internet platform can handle. It was a dynamic process, and we have bought additional licenses during the crisis.

360°: How will e-learning evolve in your university after this experience?

DW: I assume that both students and teachers will continue to do certain things digitally, based on the experiences in the last few months. We spent 20 percent of our time teaching via e-learning and 80 percent in face-to-face sessions, and now we are at 100 percent e-learning. I estimate that in the future, we will stay somewhere around 50 to 60 percent e-learning. People are different, but I assume that this is what students want. I think that a majority experienced learning at their own pace, on their own schedule as an added value, and they want to continue to work digitally.

But student coaching and the creative processes will continue to take place face-to-face in the university because it just works better this way. Everything that has to do with innovation will happen physically.

360°: Another project is the optimisation of the use of classrooms at the vocational school in Vienna. How has the project evolved due to the coronavirus pandemic?

Yulia Kartysh: We have been working for almost 20 years to improve the use of space. This is particularly important for school buildings where the whole infrastructure and the equipment are used by different student groups, one after the other or simultaneously. Eight vocational schools in Vienna will merge, and we have to find synergies to use the space more efficiently.

Our team ensured that learning, space and the room’s whole organisation are considered and optimised together.

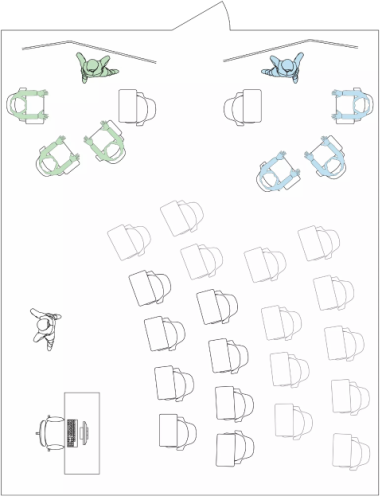

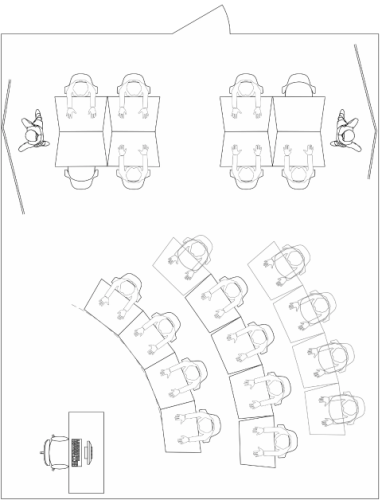

First, we investigated how learning should be organised in the future and how many lessons and forms of learning are needed. Then we tested different room occupancy plans with varying forms of space management. Learning initially remained consistent; only the room layouts were changed to see which forms of facility management support teachers the most.

Space Planning: Yulia Kartysh

Space Planning: Yulia Kartysh

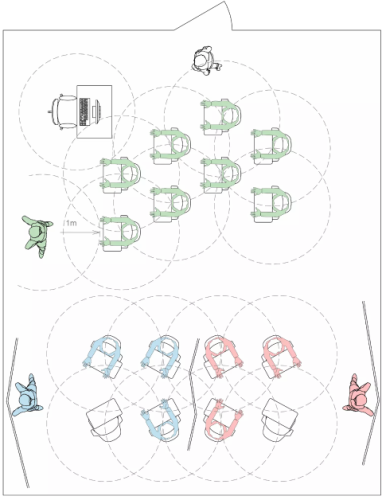

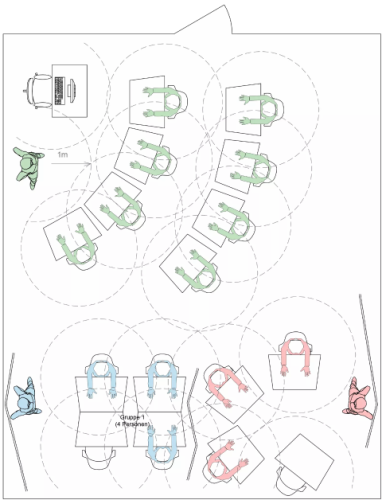

Due to the coronavirus pandemic, we had to consider the distance rules of at least one meter.

In general, class sizes range from 12 to 24 students. If we try to keep the same size, we need one third more space and additional furniture.

Especially when working in groups at large tables, it is difficult to comply with these rules without installing plexiglass panels. In German-speaking countries, such panel protection is very unusual in schools. Therefore, we recommended chairs with small individual tables in the vocational school center, making the rules much easier to respect because the tables either do not allow students to come too close to each other or can be arranged in a strategic way. An additional advantage is that they can still be used after the pandemic when distancing is no longer necessary.

Vienna’s vocational schools want to use the active-learning approach anyway, and chairs with writing tablets and small tables are particularly suitable for this.

Space planning: Yulia Kartysh

Space Planning: Yulia Kartysh

360°: How do you optimise educational infrastructure through shared use by different schools?

YK: We have developed simulations to map the dynamic use of classrooms. We are working with videos where users move around and no longer with static classrooms and learning styles. This way, we can simulate a year of classroom usage based on certain parameters that we see from our current setup. We are also investigating how many classrooms are needed if each of the eight schools will allow other schools to use their rooms.

Teachers want to switch between digital and non-digital learning content during lessons.

We have looked into what the benefits might be to transform normal classrooms into digital-teaching classrooms, equipping all classrooms in the central vocational school with computers. This makes different learning activities possible in the same room, making the room much more effective.

The change in learning activities is no longer associated with the change of classrooms.

In the future, presentations, group work and individual work will take place in the same room. This makes each room a bit more expensive but saves about one-third of the space. The increased investment in IT equipment and furniture will rebalance within a very short time.

360°: How will the coronavirus crisis affect education and learning environments in general?

YK: The crisis has triggered an enormous boost to modernize teaching and learning. Before the corona pandemic, the vocational schools in Vienna told us that they would like to introduce more self-determined learning. Still, they said this was not possible because many students are simply not able to learn in a self-determined way.

But during the crisis, teachers noticed that self-determined learning is working very well for about 90 percent of all apprentices.

Some students had problems because they didn’t have laptops or internet access, but modern forms of learning are definitively possible in vocational schools. Currently, the question is whether schools are places for individual learning, or whether pupils should learn independently at home.

Many consequences of the corona pandemic will stay and change the organisation of learning and learning spaces in the future. Vocational schools are becoming more and more similar to companies, as company work processes are trained there. As a result, learning spaces at vocational schools will slowly evolve towards organizational architecture. Universities will change significantly because of the crisis, and we will need less space overall.

In the future, universities will be used much more as a workshop platform for collaboration and innovation, and I assume that lectures in the lecture hall will soon be gone.