Futureproof Your Work

Why COVID-19 is shining a light on how our humanity is tied to the workplace.

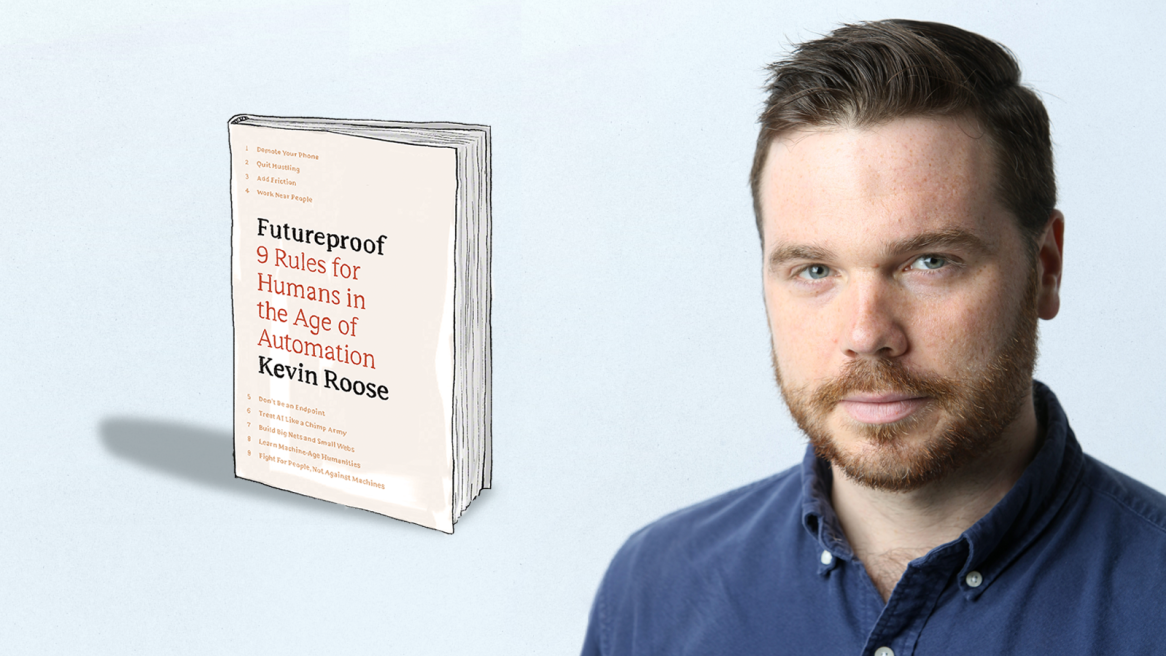

New York Times business, technology and culture columnist Kevin Roose has spent years researching what separates the way humans and machines add value to their respective work. He recently finished his book “Futureproof,” a guide for people who want to safeguard their careers from automation (now scheduled to publish in January 2021). And on March 10, relatively early on in the quarantine within the U.S., he wrote “Sorry, But Working from Home Is Overrated” based on his research. He also hosts the Times’ technology podcast “Rabbit Hole.”

Roose cites the importance of collaboration, creativity and the physical connections we make in the workplace as critical to futureproofing ourselves in his soon-to-be published book. He spoke with 360 from his living room in the California Bay Area about why we can’t lose our humanity at work.

360: Why do you zero in on working with other people as a key element to helping us thrive in the machine age?

Kevin Roose: One of the big questions I had as I studied artificial intelligence and machine learning was: What kind of work has the best chance of surviving through this fourth industrial revolution? Almost universally, experts told me it was work that requires physical proximity, based on the value of human interaction. Customer service representatives, care workers, psychologists, teachers will all be hard jobs to fully automate because the value is not just transactional, the value is in the human interaction. So, part of my thesis around A.I. and futureproofing ourselves and our careers is that work that is social and requires collaboration is going to be harder to automate and will be a safer harbor for workers.

360: How does remote work fit into what you’ve discovered about the future of work?

KR: In a lot of ways, remote workers are halfway automated. You are a green dot in a Slack channel or a floating head in a Zoom call. Kids have already started automating themselves in their Zoom classes. They create a video of themselves nodding and hold it up to the camera. If most of your work consists of doing a process or a task remotely, you’re losing this whole other category of work that is really the place most of us are going to end up.

Remote workers are not only putting themselves at risk of being replaced by a robot, but they are also putting themselves at greater risk of being replaced by another person. If you go remote, the number of competitors for your job has now expanded to everyone in the world. For a lot of workers, it may be more comfortable to be at home, but if you’re thinking strategically about your future, you’re going to want to be in the office.

And, obviously, it has to be safe to do that. But I think this pandemic could set the remote work trend back in the end. I think a lot of people will associate remote work with fear and anxiety, constant distraction from kids, partners and family, with not being able to separate work from life. So, I think a lot of people will rush back to the office when this is over.

360: Why did you decide to write “Sorry, But Working from Home Is Overrated?” for the NY Times?

KR: I’ve been doing research on workplace trends, productivity and organizational psychology for my book. Part of what interested me was this question of what we gain or lose from a centralized office setting to a more remote work policy. Some companies say they’ve never been more productive, others say they can’t get anything done. People are getting burned out on Zoom meetings. I noticed that in almost all of the studies that showed a benefit to remote work, those were mostly benefits from the perspective of the employer. Work from home tends to be very good for bosses.

There are a lot of people right now projecting that we’ll never go back to offices and I find that totally ludicrous, totally implausible. I think some number of people will continue to work from home. But, I think a lot of people are really struggling. Not just parents trying to balance caretaking with work, but also people like me who find it impossible to separate your work from your life. What the research has found is that people who work from home tend to work longer hours, take fewer sick days and report feeling less satisfied with their work.

360: What did you find was the organizational impact of remote work?

KR: A lot of studies have found people who are co-located tend to be more creative, solve problems more quickly and the quality of their output is higher. That research is decades old and pretty consistent. I live and cover Silicon Valley and a lot of tech companies that make the software that allows for remote work do not have large remote workforces during normal times. Google and Apple, these companies emphasize in-person collaboration. The reason is they’ve found the quality of people’s work gets higher when people bump into each other in the lunch line, the kitchen pantry or the hallway. People who study organizational psychology say serendipitous interactions have a large impact on problem solving and creativity.

360: Have you found collaboration to be a muscle we can lose if we pull back from it?

KR: Absolutely. There’s some fascinating research around technology use and emotional intelligence. One UCLA study compared a group of kids who went to a nature camp for five days without devices to a group that stayed at school with normal access to their devices. They were tested before and after for signs of emotional intelligence; observing body language, discerning feelings and reading emotional situations. They found the school group flat-lined, but the other group dramatically improved their emotional intelligence. That tells me we do have to practice these skills of interpersonal relationships, collaboration and discerning group dynamics. It’s something we have to work on just like we have to go to the gym.

360: Can you share some of the research behind the concept of “human premium” that you write about in your book?

KR: Throughout human history, we shift value to the tasks humans can do and machines cannot. That’s why TVs that used to cost $2000, now cost $200. But, if you want to buy a set of hand-blown glassware that’s going to cost you more. The more evident the human connection is in something, the more value we place on it. There’s an interesting study that reinforces the value we place on human connection. People all received a randomly-selected bag of candy, but one group got an added note that said, “Hand picked for you.” Those people described the candy as tasting better even though it was the same. So, the way to think about this is to try to make it very clear in whatever your output is that a human is behind this.

Roose’s book Futureproof: 9 Rules for Humans in the Age of Automation is available for pre-order now. Learn more at kevinroose.com/futureproof.

Kevin Roose is an award-winning technology columnist for The New York Times. His column, “The Shift,” examines the intersection of tech, business, and culture. He is a New York Times bestselling author of three books, Futureproof, Young Money, and The Unlikely Disciple. He hosts the New York Times podcast “Rabbit Hole” and is a regular guest on “The Daily.”