The Privacy Crisis

Although workplaces today make it seemingly easy for people to collaborate, most leaders remain dissatisfied with the pace and frequency of breakthroughs.

Taking a Toll on Employee Engagement

In organizations all over the world, people are facing brand-new problems that require sharing information and putting knowledge together in new ways. For all the right reasons, collaboration has become the big engine for progress and innovation. Although workplaces today make it seemingly easy for people to collaborate, most leaders remain dissatisfied with the pace and frequency of breakthroughs. Uncertain of what to do next, they hire new talent, carve out trendy group spaces, add technology or step up team training efforts—but still don’t see the gains they desire.

Paradoxically, most efforts to fuel more successful collaboration are only making it worse. New Steelcase research has revealed that, while togetherness at work is vital for value creation, in excess it’s a killer.

Throughout the world, too much interaction and not enough privacy has reached crisis proportions, taking a heavy toll on workers’ creativity, productivity, engagement and wellbeing.

Without question, successful collaboration requires giving coworkers easy access to each other. But it also requires giving each individual the time and places to focus and recharge, and too many workplaces today aren’t delivering on privacy as a necessity.

“The need for privacy sometimes—at work as well as in public—is as basic to human nature as is the need to be with others,” explains Donna Flynn, director of Steelcase’s WorkSpace Futures research group. “The harder people work collaboratively, the more important it is to also have time alone—to be free from distractions, apply expertise and develop a solid point of view about the challenges at hand. People also need privacy to decompress and recharge.

“A key takeaway from our study is that the open plan isn’t to blame any more than reverting to all private offices can be a solution. There is no single type of optimal work setting. Instead, it’s about balance. Achieving the right balance between working in privacy and working together is critical for any organization that wants to achieve innovation and advance.”

Desperately Seeking Privacy

More than ever before, workers are going public with complaints about their lack of privacy at work. Blogs and online chat rooms are chock-full of soliloquies about what everyday life in an open-plan workplace is like: how easy it is to be distracted, how stressful the environment can be and how hard it is to get any individual work done. Many say they literally can’t hear themselves think. Seeing the opportunity, one high-end headset brand has started advertising its products as a way to hear your favorite music or simply to hear the sound of silence instead of your coworkers. But what the ad doesn’t say is that wearing headsets cuts people off from hearing and engaging in conversations that could be valuable for their work, thereby eliminating a potential advantage that open-plan workspaces are intended to provide. And audio distractions are only part of the problem.

Meanwhile, beyond the chatter of cyberspace and advertising, other strong signals have been mounting that workers’ lack of privacy is a problem that needs C-suite attention ASAP.

Gallup’s recent report on the State of the Global Workplace found only 11 percent of workers around the world are engaged and inspired at work, and 63 percent are disengaged—unmotivated and unlikely to invest effort in organizational goals or outcomes. But slicing the data shows that, at least in the United States, those who spend up to 20 percent of their time working remotely are the most engaged of all workers surveyed. This finding suggests that these engaged workers are able to balance collaboration and interaction with colleagues at the office and are working remotely to achieve the privacy they need for some of their individual work. And yet, many business leaders recognize that sending people home anytime they need privacy isn’t efficient and it can threaten versus strengthen innovation by diluting the cultural “glue” that inspires workers and keeps them connected to the organization’s goals.

Moreover, a recent Steelcase study of the workplace conducted by the global research firm IPSOS of more than 10,500 workers in Europe, North America and Asia confirms that insufficient privacy in the workplace is an issue throughout the world. The survey results show that being able to concentrate, work in teams without being interrupted or choose where to work based on the task are frequently unmet needs.

Yet the 11 percent of workers who had more privacy and were more satisfied with their workplace overall were also the most engaged. Conversely, employees highly dissatisfied with their work environment were the least engaged. This study confirms observations by Steelcase researchers: The workplace has a very real impact on employee engagement.

Workplace satisfaction bolsters employee engagement

A Steelcase survey conducted by the global research firm IPSOS shows a strong correlation between employees’ satisfaction with their work environment and their level of engagement.

Only 11 percent of respondents were highly satisfied with their work environment; they were also the most highly engaged. These respondents agree their workplace allows them to:

| 98% | concentrate easily |

| 97% | freely express and share ideas |

| 95% | work in teams without being interrupted |

| 88% | choose where to work within the office, based on their task |

| 95% | feel relaxed, calm |

| 97% | feel a sense of belonging to their company and its culture |

Cost of disengagement

| USA | $450 – 550B |

| Germany | €112 – 138B |

| Australia | $54.8B |

| United Kingdom | £52 – 70B |

2013 State of the Global Workplace Report, Gallup

An Epidemic of Overwhelm

One condition that impacts workplace satisfaction and thus engagement is when employees have no choice but to work in environments that are saturated with stimuli. According to Susan Cain, author of the bestseller, “Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World that Can’t Stop Talking,” many people perform best without others around them constantly. Despite this, she contends, teamwork is often elevated above all else. The result can be a psychological phenomenon that has been coined as “groupthink”—people’s natural inclination to succumb to peer pressure and go along with others rather than to risk being isolated by contributing a differing point of view.

The way forward, according to Cain, is “not to stop collaborating face-to-face, but to refine the way we do it.” Instead of providing only open-plan work settings, Cain urges organizations to “create settings in which people are free to circulate in a shifting kaleidoscope of interactions,” and then be able to disappear into private spaces when they want to focus or simply be alone. Read how Susan Cain and Steelcase have collaborated on a collection of Quiet Spaces in Quiet Ones.

David Rock, a performance management consultant and author of “Your Brain at Work,” points to the latest findings from neuroscience. Most workers, he says, are suffering from “an epidemic of overwhelm” due to huge increases in the amount of information we’re expected to deal with every day and a significant increase in the distractions that come our way. Science has shown that the human prefrontal cortex, where most knowledge work processes take place, is small, energy-hungry and very easily distracted, Rock notes. Many researchers’ work has proven that any belief that people can successfully multitask is essentially wishful thinking. Humans can give controlled, full attention to just one thing at a time. When we try to pay attention actively to any two memory-dependent tasks at once, we’re easily distracted and end up doing neither one well. Given this reality, achieving peak performance in today’s work environments has become much more challenging than it was even just a few years ago.

“As we got better at sharing information and building software and techniques and tools for collaborating, we’re leveraging the fact that information travels literally at the speed of light… And so with all this efficiency of information flow and of communication, we’re hitting up against the final bottleneck, which is our ability to pay attention and make decisions. In the average morning download of emails, many people have to process in a half hour what your brain probably needs a day or two to process at the right kind of pace… We’re definitely stretching our capacities in some challenging ways,” says Rock.

Find out more about this subject in the article Q+A with David Rock.

Office workers are interrupted as often as every three minutes by digital and human distractions. These breaches in attention carry a destructive ripple effect because, once a distraction occurs, it can take as much as 23 minutes for the mind to return to the task at hand, according to recent research done at the University of California.

The problem, Rock explains, is that the network in the brain that controls impulses —known as the brain’s braking system—is easily tired. This means that once we’re distracted by something, it’s harder to stop ourselves from being distracted by something else. He makes the comparison of using your foot as a brake on a motorcycle. “Your foot is very effective until you start to move. It’s a little bit like that with distractions. Before you’re distracted, you can stop yourself from being distracted. But once you start being distracted, once you start moving, your brakes don’t work very well.”

The consequences of distraction

- 11 mins for interrumptions. When we try to work on a project, we get interrupted every 11 minutes (on average).

- 23 mins to return to FLOW. When we get interrupted, it takes us up to 23 minutes to get back into FLOW —the state where we’re deeply engaged.

- 5 IQ points for multi-tasking. When women are multitasking cognitive capability is reduced by the equivalent of 5 IQ points.

- 15 IQ points for multi-tasking. When men are multitasking cognitive capability is reduced by the equivalent of 15 IQ points.

Researchers’ work has proven that any belief that people can successfully multitask is essentially wishful thinking. Humans can give controlled, full attention to just one thing at a time. When we try to pay attention to any two memory-dependent tasks at once, we’re easily distracted and end up doing neither one well.

Overexposed?

Spatial perceptions have played an important role in the survival of the human race, and significant implications from our evolutionary past remain rooted in our psyches today.

“We prefer landscapes that give us a clear view of what’s happening around us —open places that offer a broad vantage as part of a group — as well as ready refuge places where we can hide if needed,” explains Meike Toepfer Taylor, a Coalesse design researcher. In other words, while the watering holes and caves of our ancestors have been replaced by gathering places and private enclaves in our offices today, people’s needs for both types of settings are basic and instinctive.

“External distractions —things like sound or what we see— can be controlled in the environment, but it’s really up to each individual to figure out how to control internal distractions. A big insight from our research was that the way each person controls distractions is very different.”

Donna FlynnDirector of Steelcase's WorkSpace Futures

For many companies, it now appears that there is too much emphasis on open spaces and not enough on enclosed, private spaces.

“A lot of businesses are now struggling with the balance of private and open spaces,” says Flynn. “There’s mounting evidence that the lack of privacy is causing people to feel overexposed in today’s workplaces and is threatening people’s engagement and their cognitive, emotional and even physical wellbeing. Companies are asking questions like, ‘Have we gone too far toward open plan… or not done it right? What’s the formula? What kind of a workplace should we be creating? ’”

As a human issue and a business issue, the need for more privacy demands new thinking about effective workplace design, says Flynn.

Most people think about privacy in terms of other people bothering us, but it’s really about control, say Steelcase researchers.

“When Steelcase started looking into privacy in the early 1980s, our researchers were primarily exploring spatial properties, especially the analytics of sound management. By the early ‘90s, they had synthesized a solid understanding of four mechanisms that regulate privacy in the physical setting: acoustical, visual, territorial and informational. In other words, privacy in any setting is determined by what you hear, what you see, how you define your boundaries and/or what kind of information is revealed and concealed.

“External distractions —things like sound or what we see— can be controlled in the environment, but it’s really up to each individual to figure out how to control internal distractions. A big insight from our research was that the way each person controls distractions is very different.”

Donna FlynnDirector of Steelcase's WorkSpace Futures

“But now we live in an online world as well as a physical one. At the same time that it’s brought us closer, technology has invaded people’s privacy, exacerbating concerns and sensitivities. We wanted to know more about current human needs for privacy and the types of privacy experiences that are important to workers today. We realized we needed to look deeper and apply a new lens,” explains Melanie Redman, a member of the Steelcase WorkSpace Futures team that recently researched privacy by surveying, interviewing and observing workers in North America, Europe and Asia.

Privacy in Physical Settings

According to Steelcase research, people instinctively evaluate four, often-overlapping mechanisms that determine if a space can provide the type of privacy experience they seek:

Acoustical privacy:

Undisturbed by noise and/or able to create noise of your own without disturbing others.

Visual privacy:

Not being seen by others and/or freeing yourself from sight-induced distractions.

Territorial privacy:

Claiming a space and controlling it as your own (olfactory privacy is a subset).

Informational privacy:

Keeping content (analog and/or digital) and/or a conversation confidential.

As a result of their work, the Steelcase researchers framed the basic psychological context for individual privacy into two spheres: information control—what others can know about us—and stimulation control—managing distractions. They found patterns that were consistent globally: Today’s workers repeatedly shift between revealing and concealing themselves, and between seeking stimulation and blocking it out.

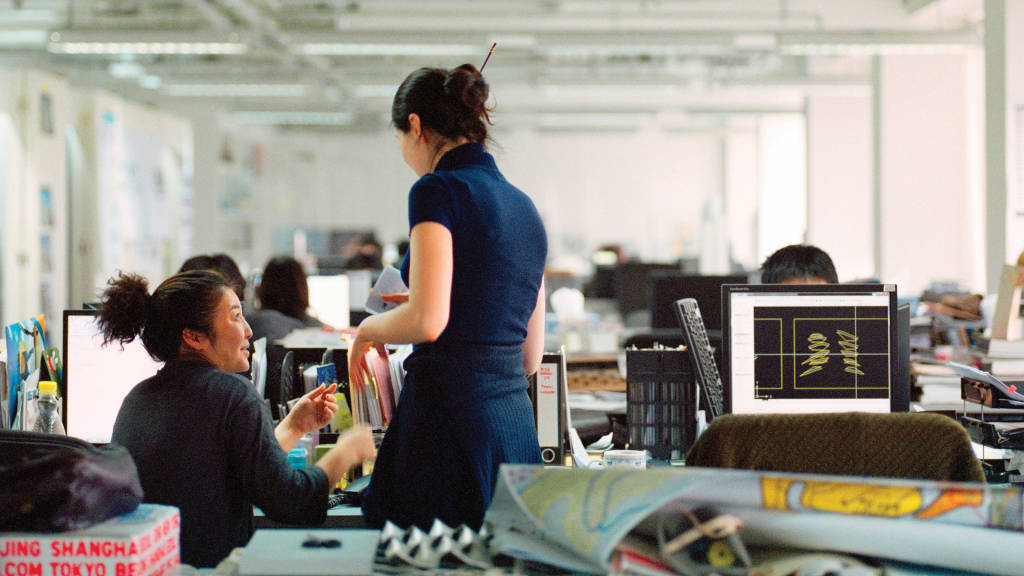

“The most surprising thing to us was how universal the need for privacy is in today’s world. We expected that in countries like China, which has a very collectivist culture, privacy might be less of a need than in countries like the United States, where individualism is prized. But what we discovered is that people all over the world want privacy at times. In different cultures, they may seek it primarily for different reasons and in ways that are permitted in their culture, but the need for privacy sometimes—at work as well as in public—is as important to people as is the need to be with others,” says Wenli Wang, who conducted Steelcase’s privacy research in China.

People in Western countries seek privacy at work most often in order to manage distractions, whereas in China the primary motivation is to keep information and one’s self outside of others’ sight, explains Wang. “In China, people don’t think about individual privacy in the same way that Westerners do. In the Western world, it’s more often about stimulation control. Being distracted isn’t as much of a talking point here in China. It’s more about information control, keeping personal information from others and getting away from other people watching you. That’s challenging at work because workstation density is fairly extreme and there typically aren’t options inside the workplace for taking a personal call or having a personal conversation.”

Privacy: A Timeless Issue

The clamor for privacy at work isn’t new. In fact, office design concepts have been oscillating around it for decades. Open-plan systems furniture, developed in the late 1960s to accommodate a burgeoning office workforce, was envisioned as a way to provide more privacy than the rows of desks in large rooms where non-management people had typically worked in the past. Of course, it optimized real estate and reduced costs, too. Over time, the approach continued to evolve. In North America many organizations intentionally migrated to cubicles as a way to flatten hierarchies, break down functional silos, improve collaboration and create a more team-driven organization.

To better understand changing needs and expectations for workplace environments, Steelcase commissioned the opinion research firm of Louis Harris and Associates, Inc. in 1978 to conduct a pioneering study of the attitudes of office workers, corporate office planners and professional office designers toward their offices. The results showed that privacy-related considerations were very important to office workers and were, in general, the least satisfactory aspects of their work environments. Though privacy remained an issue, another study in 1991 revealed that changes were underway: Office workers were spending more than half of their time working alone, but organizations were beginning to respond to the growing need for faster, better and more efficient work outputs, and getting to those goals required more collaboration. More workers in 1991 reported there were areas where they could get together to meet and talk informally than two years previous (51 percent vs. 46 percent in 1989), while 57 percent said specific project areas were available.

Throughout the ‘90s collaboration got stronger and the pendulum began swinging away from privacy. Based on an another survey that Steelcase conducted in 2000, nearly half of workers (48.9 percent) wanted more access to others in their work environment, compared to just 27 percent that said there was too little privacy. What’s more, one in every 10 respondents (9.6 percent) said their organization’s work environment had too much privacy.

The value of collaboration has become so recognized since the early ‘90s that, especially in the tech sector, creative industries and countries with egalitarian cultures such as The Netherlands, even executives have chosen to leave their private offices in favor of open plan settings that offer the reward of sharing information more easily for better, speedier decisions.

Today an estimated 70 percent of office spaces in the United States have some form of open plan, according to the International Management Facility Association. Over time, these workstations have become more open and considerably smaller. In North America, the amount of space allotted per worker has decreased from an average of 500 square feet per person in the 1970s to 225 square feet in 2010 to 176 square feet in 2012, says CoreNet Global, and it’s predicted to drop as low as 100 square feet by 2017. At the same time, panel heights have gone down from a standard of 5-6 feet to four feet—or less. And in many offices today, panels have disappeared altogether in favor of open

“bullpens” or benching work environments, often used on a shared “hot desking” basis versus individually assigned.

Although technology has made work more mobile, the majority of workers worldwide are still doing most, if not all, of their work in workplaces with still-shrinking personal space and few, if any, accommodations for privacy. Meanwhile, the work they do has become more complex and fasterpaced to meet the imperatives of creativity and innovation that rule today’s economy.

“There really is no one-size-fits-everybody-all-the-time solution. Privacy encompasses many different needs and behaviors.”

Melanie RedmanSenior Researcher, Steelcase

How people use space as an extension of culture has been studied in-depth since the early 1960s. An American cultural anthropologist, Edward T. Hall, coined the term proxemics (the study of human spatial requirements and its effect on communication, behavior and interactions) and established it as a subcategory of nonverbal communication. Hall investigated spatial zones based on the amount of distance between others and ourselves: intimate space, personal space, social space and public space. Each is considered appropriate for different situations, and personal space is where people feel comfortable working with others. While the specific distances vary some, each national culture has spatial norms for each of the four zones. In North America, for example, intimate space extends 18 inches from the body, while personal space extends out to 4 feet, social space to 12 feet, and the public zone is beyond that.

Some of the stresses of today’s work environments can no doubt be traced to the fact that people’s personal space is being compromised. Many are working in environments that routinely bring coworkers close to or even within intimate range, says Taylor. This invasion is not only occurring in physical space. It’s also happening digitally when people make video calls on their mobile devices, which puts the other person less than an arm’s length away. In contrast, a videoconferencing configuration that situates distributed team members “across a shared table” makes for a much more natural and comfortable exchange among peers.

“As someone who grew up in the U.S.’s deep south and now living in Shanghai, I’m fascinated by how much people are different and how much they are alike.”

Wenli WanSteelcase

Though there are culturally based differences regarding privacy and acceptable ways to achieve it, Steelcase’s work with global companies has shown that organizational protocols usually trump nation-based norms fairly quickly, says Redman. “If a company places a high value on collaboration and designs an open, collaborative environment in a location where the local culture doesn’t support those behaviors, it may wonder why those local employees don’t like their new office,” she explains.

Within any given culture, the researchers emphasize, privacy is always ultimately contextual to the individual. This means that the privacy that each person seeks depends on personality, state of mind at the moment and the task at hand. “While a particular environment may provide the stimulation necessary for creative work on one day, that same environment may provide only distraction the next day,” says Redman. Moreover, says Wang, Steelcase’s research underscored that mental privacy and physical privacy, though often related, aren’t necessarily synonymous. “People talked about having their own ‘space’—i.e., their own headspace, with the freedom and safety to do and think whatever they want without judgment.”

Five Privacy Insights

“When people say they need some privacy, it can mean very different things. By diving deeper into the experiences that people seek out for privacy, we were able to identify five key insights,” says Redman. “As an output of our research, we coded these five key insights into a set of principles for experiencing individual privacy. Examining each of the five principles on its own is a pathway for gaining a deeper understanding of human privacy needs.”

By synthesizing findings from academic studies with their own primary investigations, Steelcase researchers identified and defined these five privacy experiences:

1. Strategic Anonymity: Being Unknown / “Invisible”

The ability to make yourself anonymous is a key aspect of privacy, in that it frees you from the restraints incurred through normal social surveillance. Being unknown allows people to avoid interruptions, as well as express themselves in new ways and experiment with new behaviors. The key is that it’s strategic—individuals choosing when and why to make themselves anonymous. For instance, when people go to a café to get focused work done, they are often seeking to block the social distractions of the workplace. The low-level vibe of strangers can be just right to stimulate thinking without attention becoming diverted.

Examples:

- Going to work at a café or other place where you’re unknown

- Engaging in online discussions using an avatar or handle

2. Selective Exposure: Choosing what others see

Our innermost thoughts and feelings, our most personal information and our own quirky behaviors can only be revealed if we choose to do so. People choose to reveal some information to certain people or organizations, while revealing different information to others. Identity construction is a well-established concept in the social sciences, recognizing that people represent themselves differently to different people. Today, as personal information is being shared across new channels, people are raising new questions about what’s “safe” to divulge. While the decision to share information involves the weighing of benefits and risks, the choice is different for each person. Culture, gender and personality influence the choice through implied permissions or inhibitions, as well as personal comfort. Behaviors that are permitted in one culture—such as naps at work in China or relaxing with wine at lunch in France— may be frowned upon in other parts of the world.

Examples:

- Opting for a telephone call instead of a video conference

- Choosing which personal items to display in a workstation

3. Entrusted Confidence: Confidential Sharing

Privacy isn’t just about being alone. We also seek privacy with selected others. When we choose to share personal information or our emotions with someone else, there is a measure of trust involved—an assumption that the other person understands that the shared information isn’t for general public consumption. There are many instances in daily work when small groups—two or three people—want to confer. But in today’s mostly open-plan workplaces, it’s difficult to find places where such conversations can occur without being scheduled. In too many cases, this reality translates to lost opportunities.

Examples:

- Discussing a personal situation with a colleague

- Being in a performance review with your manager

4. Intentional Shielding: Self Protection

Personal safety isn’t just about protection from physical harm. There is a strong psychological component, as well. The feeling of personal invasion that people report after a home break-in indicates the close connection between personal territory and sense of self. We take active measures to protect ourselves from such intrusions. Though less traumatic than a theft of personal belongings, people experience similar feelings of invasion at work and seek ways to protect themselves from distractions and prying eyes. Self protection may also involve developing a point of view without the distracting influence of groupthink so that, when the group comes together to collaborate, individuals can bring stronger, more compelling insights to the challenges at hand.

Examples:

- Wearing headphones to block out, audio distractions

- Sitting with your back against a wall

- Hiding your computer screen

5. Purposeful Solitude: Separating Yourself

Isolation is a state of mind—it’s possible to feel isolated from a group while that group surrounds you. But solitude is physical: intentionally separating from a group to concentrate, recharge, express emotions or engage in personal activities. People in individualistic cultures, such as the United States, may take times of solitude almost for granted, but even within a collectivist culture, such as China, being alone sometimes is a fundamental need.

Examples:

- Finding an enclave

- Going outside

- Sitting in the farthest empty corner of a large room

The Privacy Paradigm

As the researchers synthesized their work, it became clear that supporting people’s privacy needs in the workplace requires a diversity of environments.

“There’s a tendency to think about privacy primarily in terms of the private office. This paradigm has been embedded in workplace design,” says Flynn. “Our research confirmed that people seek privacy for various reasons and they want it for a variety of timeframes. Sometimes it might mean finding a place to sit down and focus for an hour, sometimes it might mean just being quiet for 20 minutes between crazy meetings to calm the mind and still your thoughts. We see opportunities to reinvent private spaces within the entire workplace landscape, to offer spaces that can be very personal and personalized for someone when they need it. Having choices and some control over your experiences at work is really key for people’s wellbeing and performance.”

“Privacy isn’t always about four walls and a door. ” says Redman. “You can have a measure of privacy with two walls, you can have privacy in open spaces. It depends on what kind of experience you’re looking for. ”

“What’s been overlooked in the push for collaborative work is the value of individual time.”

Donna FlynnSteelcase

Even if not enclosed, informal settings that attend to human needs in obvious ways can feel more private than impersonal, institutional environments. Something as simple as high-back lounge seating can envelope a person in a semi-private cocoon.

For most workers, privacy needs ebb and flow throughout the day as they toggle between collaboration and tasks that require shallow individual focus, such as routine emailing, and those that require deep individual focus, such as analyzing data or creating something new. Mihaly Csikszentmihaly is prominent among psychologists who say humans are wired to seek deep absorption in complex challenges, achieving a state of consciousness that he described as flow. Of course, for individuals and teams, privacy alone can’t ensure flow, but the lack of privacy can obviously prevent it.

As much as people are wired for individual achievement, they’re also wired to crave collaboration. Working in privacy all the time can have as many negative impacts on performance as always working in collaboration, and also carries as many health risks as smoking, says David Rock.

Social interactions are a delicious thing to the brain…,” he explains. “Your brain loves interaction with people, it’s a very important part of keeping ourselves alive.”

Because our brains are deeply social, if someone walks past our desk, we can’t help but look up, he notes. “It’s a knee-jerk reaction. So whether it’s someone walking past your desk or someone sending you an email, these distractions are much too powerful to avoid. So we need to create time and space to switch these things off and do deeper thinking… If we talk about pure collaboration, we see it’s actually about being able to come together and make thinking visible, and also being able to go away and do quiet work and then come back together. So the opportunity is to be able to reflect and then regroup, reflect and regroup.”

Because human needs for privacy and togetherness are yin and yang —essentially different but also complementarily linked —there is no single type of optimal workspace.

“What’s been overlooked in the push for collaborative work is the value of individual time in contributing to the collaborative effort,” says Flynn. “The value of collaborative work isn’t going away. Our research has shown that when you have diverse minds coming together to solve a problem, you tend to solve that problem with a higher-quality solution. But we need to recognize that collaboration 8-10 hours a day is going to lead to burnout. The way to support people is to provide the ability to move between individual time and collaborative time, having that rhythm between coming together to think about a problem and then going away to let those ideas gestate. That’s a really important, basic human rhythm.”

“We need to find the balance between the two ends of the spectrum,” she continues. “The future is really in that balance because people are going to continue to be mobile, people are going to continue to be augmented by technology and that’s going to drive the need for even more individual choice-making across the spectrum.”

“The way to support people is to provide the ability to move between individual time and collaborative time, having that rhythm between coming together to think about a problem and then going away to let those ideas gestate.”

Donna FlynnSteelcase

Creating a New Ecosystem

A challenge for enterprises today is understanding people’s individual needs in the workplace. Especially because we’re now saturated with technology connections as well as in-person connections, most of today’s workers are operating in a dense informational landscape. Gaining the broad perspective of collaborative work is more important than ever. At the same time, this intensity makes having places for private refuge more important, too.

People are social creatures. We don’t like to be ostracized. So when we’re in a group setting, our brains will easily change our minds to agree with others. That’s a danger of constant collaboration. It’s very important to also give people the chance for privacy, so they can form their own ideas to bring to the group.

Melanie Redman

Achieving the right balance between privacy and collaboration is fundamentally about empowering individuals with choices and some measure of control over their environment.

No single type of work environment can provide the right balance between collaboration and privacy. But when workers can choose from a palette of place —an ecosystem of interrelated zones and settings that support their physical, cognitive and emotional needs —they can draw inspiration and energy from others as well as be restored by the calm of privacy.

Finally, the workplace needs to accommodate for a palette of presence —to allow teams to connect easily both in person and over distance through technology-based communication options to match their collaboration needs and their privacy boundaries.

Insight from research suggests that fulfilling work is defined by opportunities and experiences that enable people to do their best work, acting alone as well as engaging in collaboration with others. Throughout the world, there’s growing awareness that privacy at work shouldn’t be rationed as merely a symbol of status or a reward for a select few who are given private offices. Instead, by providing places for moments of privacy for all workers throughout the organization —in every country, every position and every demographic — enterprises can realize significant rewards: higher engagement, stronger collaboration, better productivity, improved worker wellbeing and, ultimately, innovation at the pace and scale that defines business success today.

The Privacy Solution

Optimizing Your Real Estate to Give Employees Greater Choice and Control

Although privacy is a universal need in workplaces, personal preferences, spatial contexts and cultural norms are key factors for successfully designing environments for privacy, say Steelcase Advanced Applications designers.

Highly differentiated settings ensure that users can choose their best place based on task, mood and personality, making the experience of privacy personal. Context is a key consideration; the same type of privacy setting can provide very different experiences depending on its adjacency, location and level of exposure to what surrounds it. Context determines what type of boundary will be most successful in any given location and, therefore, how much the spaces will be used. Cultural values and perceptions—both geography-based and organizational—must be respected and enabled within the design.

It’s important to keep in mind that boundaries to private spaces can be open, shielded or enclosed, to support individuals working alone or together in teams. In addition to having spaces for personal retreat, being able to have private conversations or do focused work together are important dimensions of workplace privacy; meeting the full range of privacy needs requires providing for pairs or small groups as well as individuals. Planning should also recognize that, when supported by strong organizational protocols, personal privacy can be achieved in designated “together” spaces.

Privacy Distribution Framework

Inspired by our research, we have identified several different planning approaches that solve for privacy within a workplace floor plan. The best option for any organization depends on its culture, workforce mobility strategy, processes, protocols and real estate holdings:

Distributed Model.

Distributed private spaces embedded throughout a workplace provide on-demand privacy experiences, in which workers can switch between collaborative and focused modes of work rapidly with the convenience of readily available “escape places.” Adjacency to traffic paths is a key attribute of this approach, and quantity and variety are other important considerations.

Zone Model.

A separate zone space serves as an exclusive privacy hub, much like the quiet zone of a library. This approach supports planned, longer-duration privacy experiences with a portfolio of settings. In addition to variety, the success of a destination space depends on users’ respect for privacy protocols that reflect the organization’s commitment to its importance.

A combination of the distributed and zone models provides the best of both approaches: convenient access to on-demand privacy and the ability to plan ahead for guaranteed privacy as needed.

Focus Enclaves

With focus as the task at hand, space to tune out the buzz of the open space and be present in the tasks at hand is invaluable.

Embedded within a zone this shared focus space is available on demand or scheduled in advance for anywhere from short or long duration. The user has control over their transparency, temperature, lighting and sound.

The user has the ability to adjust from a seated posture to standing. The chair supports excellent ergonomics and varying postures. The adjacent storage provides quick access that is flexible for the user.

- Boundary: Enclosed

- Privacy Modes: Deep focus, Rejuvenation

- Deep focus:Shallow Focus

- Posture: Task, Stool/Stand

- Privacy Principle: Selective Exposure, Intentional Shielding

- Products Shown: Gesture, Airtouch, Coalesse® DenizenTM, BFree, Gesture Stool, Coalesse® Enea Table, Sidewalk Storage

1.1 Project Space

A shared camp for dyadic work. With a quick switch between task focused work and informal lounge connection this space is very hard working and available when needed.

This space is shared and available for users to schedule for short or long durations. The users can own and manage their surroundings when needed with the technology to share seamlessly integrated.

The walls support amplification that optimizes sharing and team work while the lounge offers a place to extend the collaboration in a more informal way. The walls provide a boundary to protect the team while allowing connection to the open office space.

- Boundary: Shielded

- Privacy Modes: Deep Focus, Shallow Focus

- Posture: Lounge/Prone, Task

- Privacy Principle: Entrusted Confidence, Intentional Shielding

- Products Shown: Gesture, FrameOne Enhanced, SOTO II Worktools, Manifesto Storage, turnstone Campfire

Conference Enclave

A private place to connect virtually to one or many. This space is tailored to the individual and allows the user to be fully immersed in the meeting with easy access from the workspace.

The technology is optimized for 1-2 people to be on video. The posture and step in and out access supports meeting needs for short meetings.

The media:scape offers quick amplification and content sharing with power access. The work surface supports the users materials with a secondary surface for personal items. A stool could be included for longer duration of go without for quick connections. Lighting can be used as a signaling device.

- Boundary: Enclosed

- Privacy Modes: Deep Focus

- Posture: Task, Stool/Stand

- Privacy Principle: Selective Exposure, Entrusted Confidence, Intentional Shielding

- Products Shown: media:scape® KioskTM, SO TO II Mobile Caddy, Coalesse® SW_1TM, turnstone Campfire, SOTO II Mobile Caddy

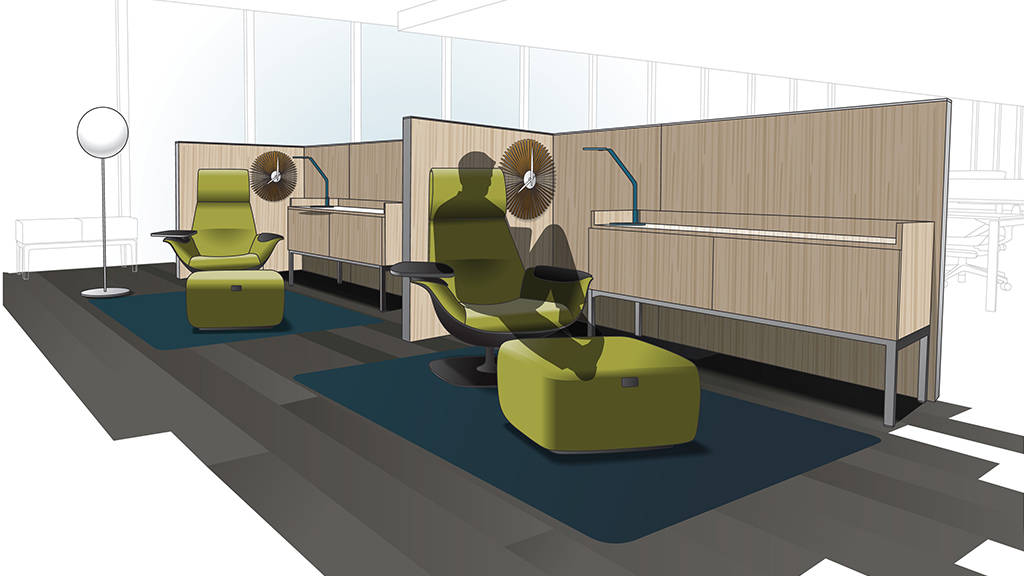

Personal Retreat

Inspiring I space that offers the ability to get away without going away, supporting mindfulness and authenticity for an individual.

With a shield to the adjacent nomadic camp the user can gain a quick reprieve, get comfortable and focus or allow the mind to wander. User has control over their visibility, access to others and choice of where to work, The space supports bringing your own technology, or simply unplugging for short term use.

The panels offer a boundary, screening interruption from adjacent work areas. The chair provides lounge posture, with a swivel base and storage in the ottoman. The storage is a place to drop your belongings with easy access and a wardrobe for coat storage. The lighting is adjustable for task use.

- Boundary: Shielded

- Privacy Modes: Shallow Focus, Rejuvenation

- Posture: Lounge/Prone

- Privacy Principle: Intentional Shielding, Purposeful Solitude

- Products Shown: Answer, Coalesse® MassaudTM, Coalesse® DenizenTM, SOTO LED Task Light

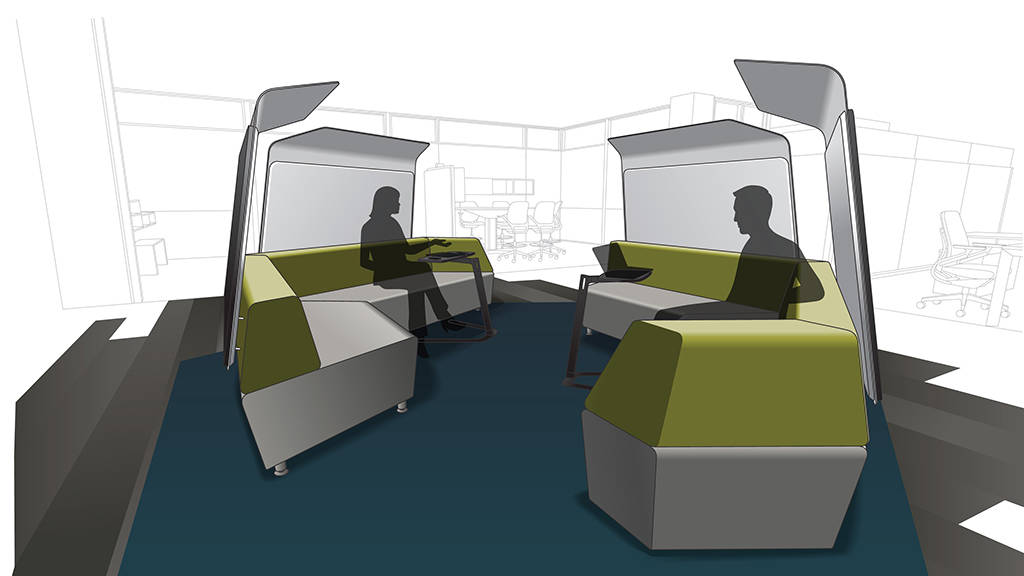

Shielded Conversation Lounge

Easily accessible, this is a place for 2-6 people to have a quick conversation without disrupting others. The canopies help contain sound, plus create visual and territorial separation from the rest of the work group. Lounge seating is comfortable and informal, and tables support personal devices and other necessary items.

- Boundary: Shielded

- Privacy Modes: Shallow Focus

- Posture: Lounge/Prone

- Privacy Principle: Entrusted Confidence, Intentional Shielding

- Products Shown: media:scape Lounge, Coalesse® Free StandTM

Connect Hub

Content sharing and face to face to interaction is optimized here.

Convenient access from meeting areas, social spaces and open plan work spaces promote an organizations best place strategy and users freedom to choose. The user has the ability to control the lighting, sound, transparency and content sharing within the space. The duration would be relatively short term, 30-60 minutes.

The walls provide a range of transparency options along with integrated technology for power access and amplification. The lounge seating also has integrated power access and inherent modularity for a flexible and customized user experience.

- Boundary: Enclosed

- Privacy Modes: Deep Focus, Shallow Focus

- Posture: Lounge/Prone

- Privacy Principle: Entrusted Confidence, Intentional Shielding

- Products Shown: turnstone Campfire, Coalesse® Circa Table

Privacy Zone 1

A privacy hub with a high degree of quiet and library vibe. A destination zone with a range of privacy experiences for the individual. The settings provide a palette for the user to select a space that best suits their needs with varying levels of enclosure, postural support, ergonomics, views and orientation.

Wood case goods and bookshelves in the space provide a familiar and comfortable setting with boundary. The furniture acts as a shield while still giving the user a sense of connectedness to the surrounding space.

Products shown:

- Open: Gesture, Manifesto, Coalesse® MassaudTM, Coalesse® Free StandTM, turnstone Campfire

- Enclosed: Coalesse® SW_1TM, Sit2Stand, Coalesse® DenizenTM, Cobi

Privacy Zone 2

A social vibe with just the right amount of stimulation provides a sense of energy through out with a choice of personal transparency. In close proximity, this privacy hub supports users seeking refuge to work individually or with one other person.

Strategic anonymity, although difficult to support on campus where users are connected to one another and generally social, could be supported here. Within this privacy hub, the culture of privacy could provide a state of being unknown or invisible.

With a variety of spaces that support 1-2 users the space is dedicated to focus and rejuvenation with a sense of energy. Areas of more or less stimulation offer users control over their environment to do things like draw on the energy of others, focus on the task at hand, or hide out.

Products shown:

- Open: Think, FrameOne Enhanced, Manifesto Storage, SOTO II Mobile Caddy, turnstone Campfire, Coalesse® Free StandTM, Coalesse® HosuTM

- Enclosed: V.I.A.

Privacy Zone 3

Balance for the user and space is about creating experiences with a range of enclosure and individual transparency.

Users can select the best place for the task at hand and manage their individual exposure with choices of fully enclosed to open, connected to or disconnected from others and active or passive rejuvenation.

Products shown:

- Open: media:scape Hoodie, Coalesse® Free StandTM, Answer, Sit2Stand, Manifesto Storage

Introducing New Research on Engagement + the Global Workplace

1/3 of workers in 17 of the world’s most important economies is disengaged, according to new research from Steelcase. Working with global research firm Ipos, the Steelcase Global Report is the first to explore the relationship between engagement and the workplace.