A Conversation with Otto Ng

Innovation and impeccable attention to detail are the keywords when it comes to design for Hong Kong-based, MIT-trained architect Otto Ng. Past projects by LAAB [laboratory for art and architecture], the multidisciplinary collective of architects, designers, engineers, sociologists and artists that he co-founded with Yip Chun Hang in 2013, include the design of a high-tech 309-square-foot home, a whimsical Opera Theatre and roof-top architecture at cultural-retail destination K11 MUSEA, and a robotic food kiosk on the Tsim Sha Tsui harbourfront.

Interview by architecture and design author and writer Catherine Shaw.

Do you remember when you first realised that you wanted to be a designer?

I don’t remember the exact moment, but I was always interested in making things and understanding the logic in how things are created and their relationship with each other. Then, when I was studying at MIT, I learned that nature is the perfect science, and technology follows nature. Architecture and art are perceived as different in some cultures, but to me they are very similar.

Do you have a personal signifier?

I have worn glasses since high school and love my Lindberg frames. They are very light, and the glass is non-reflective, which is important these days with Zoom calls. My clothes tend to be in one colour like black or navy and I usually look for a matching mask.

Favourite book?

I enjoy reading a magazine called B that covers creative brands like MUJI and Leica around the world. There are always interesting stories that you would not normally come across, and some of the brands we work with have been featured, so we find it invaluable in learning about their specific challenges and how they operate.

Favourite film?

I love the British Sherlock crime television series based on Sherlock Holmes. I really enjoy the way the stories are made up of hints that you only discover later are important. Narrative, humour and whimsy are important in our projects too, and we want to achieve that combination very naturally.

How does humour work in a creative environment?

I think that when the atmosphere is friendly, people generate exciting ideas. At LAAB we encourage all sorts of ideas, even ones that may seem impossible at first. We combine art and architecture, and having architects and artists, interior and graphic designers, and engineers working together allows us to shift positions and see design from different perspectives.

How does that work in practice?

We deliberately move staff around to different projects and focus on supporting communication. That takes them out of their comfort zones and challenges them beyond typical, clearly defined boundaries.

You are renovating your home. How does that fit in with the way you design at work?

When I co-founded LAAB, our Small Home, Smart Home project received a lot of attention. Everything was built in, so we controlled the space but, as we expand our projects’ typology, now we look at furniture in a different way. In my own home it has been hard to find the sort of furniture that I really want and so designing a range of furniture is next on our agenda. I am more aware that good design will keep for years and adapt to different homes. We are fortunate to have our own workshops so we can experiment with prototypes. You need time to use something to work out how to make it better. For instance, we recently made a Chinese candy box (pictured below), inspired by the shape of the bus stop canopy at K11MUSEA. We like transferring designs to other scales and projects to see if they work when they become something else.

What is your favourite food?

I particularly like Japanese food, not only because of the flavour, but because Japanese restaurants tend to design every detail from the space and furniture to the presentation. We like to look at different ways of doing things from Japanese to new Nordic, and then examine our own situation and find our way. I think about our Hong Kong Chinese identity and vernacular, not in the sense of repeating something obvious, but in terms of design and architecture reflecting our social and cultural norms.

Best souvenir you’ve brought home?

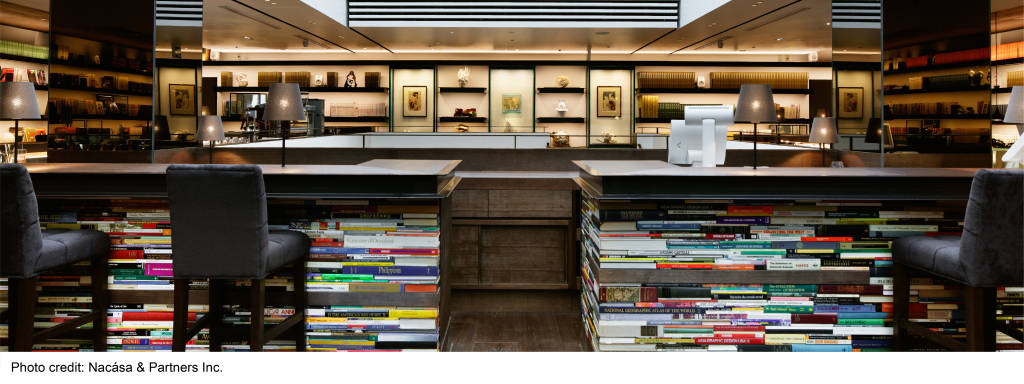

I don’t really buy souvenirs. I try to travel as light as possible and am more focused on the experience. In general, I shop cautiously because I am very aware of sustainability, and I don’t like throwing things away. I do buy books though, especially books that I can’t find online. I always schedule a full day at Tsutaya Books (pictured below) in Daikanyama, Tokyo, to buy books with interesting drawings and images that we don’t usually see online.

Are you concerned about the digital domination of visual inspiration?

Inspiration comes from the way we see the world, so I think it is a major part of why we tend to see the same things when we skim the surface. I ask colleagues not to rely on their initial reactions, which are just a departure point, but to look more deeply and understand why something is the way it is. You have to go beyond an image to find out what designers have in mind and, when it comes to architecture, remember the visuals you are looking at today were designed five years ago.

Yes, by the time we see something, it is already outdated.

It is important to look forward with an open mind. We have developed our own methodology for understanding the existing typology and for exploring how much room there is to reinvent things that are now outdated. We think about how people will experience them in five or ten years from now and then make predictions.

So many sectors of life are being disrupted. Who do you think is leading the pack in design?

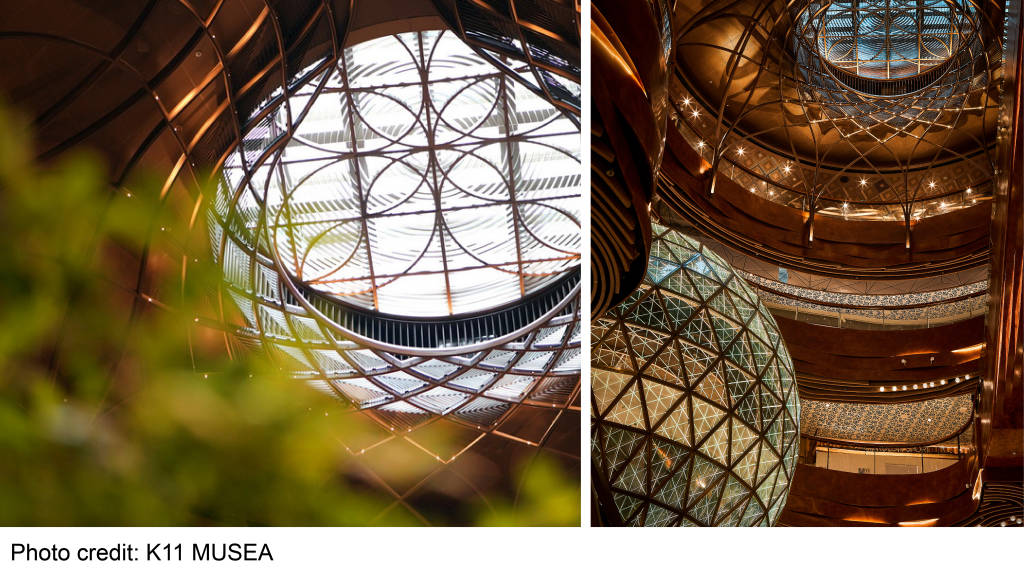

In Hong Kong, New World Development have disrupted the traditional white box retail mall concept with something very experimental at K11 MUSEA (pictured below). The founder, Adrian Cheng, has devised a different way, and now people are stimulated by nature, artistry, and technology.

Do you see technology as part of art and crafts?

I am very comfortable about knitting them together, but it is essential that the combination be seamless. You don’t just add a tv screen and tell people it is technology. I see technology as another architectural material. We want it to be embedded and feel natural.

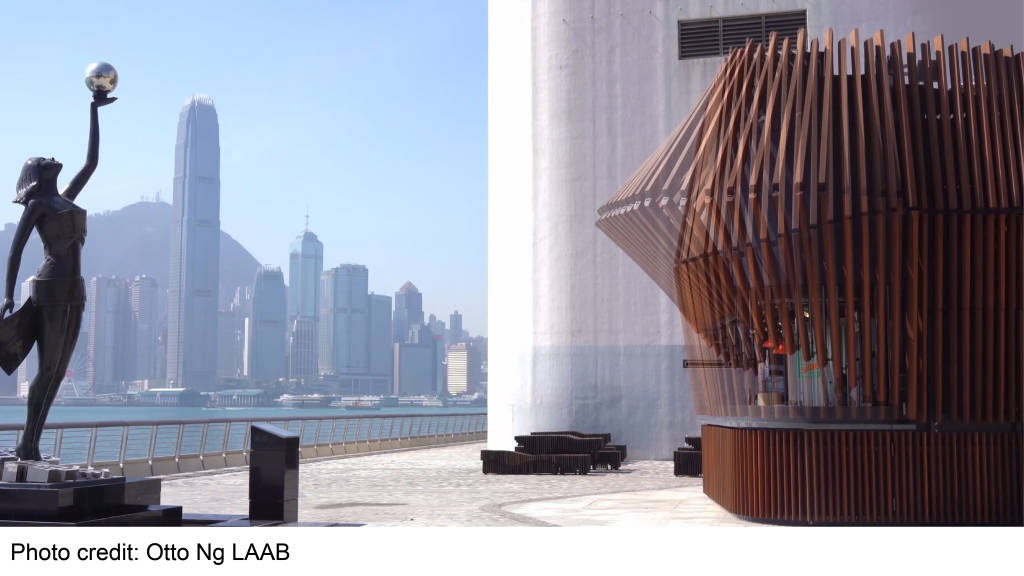

LAAB works on many scales, but what really stands out for me is the robotic architecture of the Harbour Kiosk that you designed for the Avenue of Stars. What was the inspiration for that?

I think that it feels very Hong Kong in the way it unfolds. We wanted to keep the essence of how people here occupy the street with architecture such as market stalls that expand and contract. The gate of the robotic kiosk (pictured below) is automatically transformed into an awning during the day and then returns to its original shape at night.

Your work is known for innovation and technology – how do you combine those when working on heritage projects?

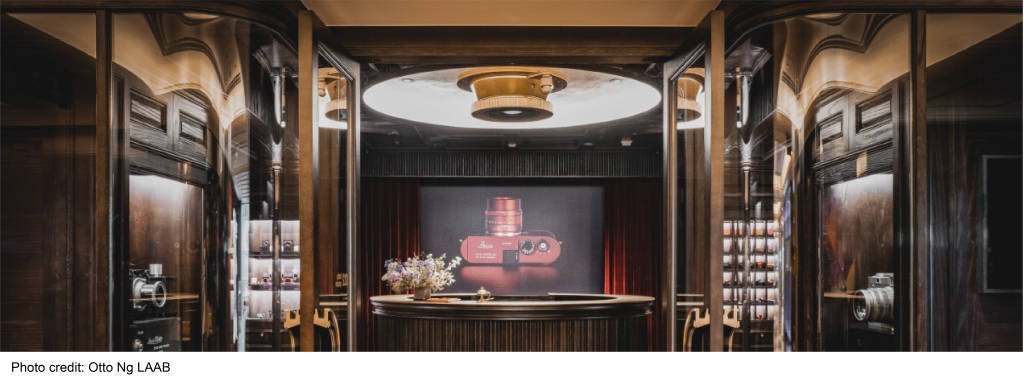

We are very interested in heritage. One of the most interesting projects we’ve worked on recently was the f22 foto space (pictured below) at the Peninsula Hong Kong. The building is 100 years old, and so is the Leica brand, and that sparked a conversation about the 1920s being a particularly interesting time for design because there were so many different movements such as Art Nouveau, the Arts and Crafts movement and at same time Modernism. This influenced our design of the gallery space in a modern setting, but the boutique is more Art Deco.

Best design advice you’ve ever been given?

Professor Carlo Ratti at MIT told me never to be afraid to ask an expert when I need to know something and to always go to the best because they are usually more passionate and interested in a good idea. No one can be an expert at everything, especially when it is complicated.

“No one can be an expert at everything, especially when it is complicated.”

Most surprising creative experience?

We’ve had a number of aha moments, but one that stands out is when we proposed a black painted brass circular staircase in the f22 foto space (pictured below). It plays with light, shadow and speed much like a camera aperture and was extremely difficult to build. Sometimes there is no manual out there, so we have to develop a design from scratch. That always turns out to be the most interesting design story.

What are you working on right now?

Our most exciting projects are still confidential, but I can say that for one, we are reinventing the typology of hotels, and for another, we are looking at opportunities and challenges in our post-COVID world.